Alexander Gorlin and

Congregation B'nai Emunah

In the spring of 1998, Congregation B'nai Emunah closed the buildings on its existing campus and embarked on an ambitious program of new construction and renovation.

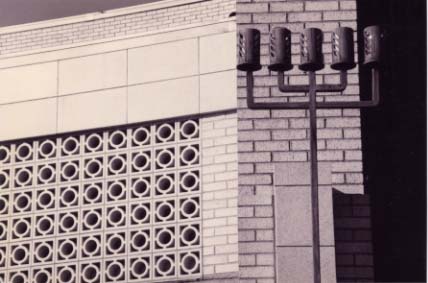

The project sprang from the prevailing sense that the Synagogue's facilities were exhausted and effectively obstructed future growth. The original Education Building on the west side of the property had structural and mechanical problems that argued against rehabilitiation. Meanwhile, the newer Sanctuary Building to the east was judged gloomy and inadequate for current needs. A haphazard hash of construction materials placed the building squarely in the late 1950s.

The Sanctuary itself was a closed box without natural light, and the seating pattern made for an alienating experience of worship. It took too many bodies to fill the pews, the room lacked clarity and a central focus, and it could not accomodate the needs of handicapped members. The whole of the project was challenging on many counts. While the congregation was willing to sacrifice the Education Building, there was a strong sentimental attachment both to the Synagogue's location in Historic Maple Ridge and, despite its shortcomings, to the Sanctuary itself.

Conceptual work on this project had begun in 1996. Early in the process, the Building Committee of the congregation laid out its preferences for bright and open spaces, warm and flexible areas for programming and informal gathering, and superb, sunlit spaces for worship. For almost a year, the Building Committee worked out its vision with a local architectural firm, laying down the basic elements of a new facility. Planning at this stage was driven by Committee members who worked out dimensions, countours, and a site map with pencil and tracing paper in hand.

With a year to go before construction was scheduled to begin, the Committee began to sense that an architect with proven synagogue design experience would be needed to shape the project as a whole. This was an important moment in the project, but the Committee quickly surveyed its options and chose Alexander Gorlin of New York City as a design architect and presiding artistic intelligence for the project.

Gorlin's work had come to the attention of the congregation through a chance encounter between architect and rabbi. The relationship was finally struck as a matter of faith and trust. Gorlin's instant and intuitive understanding of the project; his deep familiarity with Jewish forms and observances; his gentle attentiveness to the needs of the congregation; and a generous, expansive spirit resolved the anxieties of the Building Committee.

Gorlin's initial meeting in Tulsa was a bravura display of resourceful designing on the fly, patience with the Committee at its moment of decision, and a fearless willingness to take on a project that had stalled. The members of the Committee were taken with Gorlin's authority and confidence, and overwhelmed by the images in Alexander Gorlin: Buildings and Projects, the published portfolio of Gorlin's work (Rizzoli, 1997). While the architectural firm initially engaged by the congregation continued to work on construction drawings and details, the Committee transitioned to a relationship with an accomplished synagogue architect who could draw from deep reserves of imaginative strength and give the congregation a building in keeping with its expectations.

The Synagogue embraced the result with pleasure and enthusiasm. Gorlin's first sketch for B'nai Emunah was a simple arrangment of a massive arched window, flanked by two outriding squares. It suggested the defining pattern for the rest of the project and resolved a complicated problem of fenestration that had resisted solution.

More than that, it set the stage for what followed: the integration of the existing facade of the Sanctuary in an elegantly designed complex that brought to life the Building Committee's original hope. The large, light-colored volume of the Sanctuary Building is now wrapped in a cluster of smaller elements that suggest a village nestled against a hill.

Within the lively push and pull of components, there are quieting elements that create a sense of harmony and rhyme. A large copper dome on the Octagon that anchors the school building is matched by a smaller dome that greets visitors to the school. Subtle bands of brick corbeling bind the whole of the structure, and bring pleasing rhythmic change-ups to large flat surfaces.

One of Gorlin's great contributions to the project was the creation of a handsome interior courtyard. Concerned about the potential for a warren of dark and depressing spaces, he hollowed out the center of the proposed new structure and created adjoining offices and conference rooms that are now flooded with natural light. In essence, the courtyard functions as a light well, bringing the outside into the center of the project. The building would undoubtedly be burdened and claustrophobic without it. It was an important measure of the Committee's trust that it could affirm Gorlin's basic rearrangement of established spaces at a date far into design development.

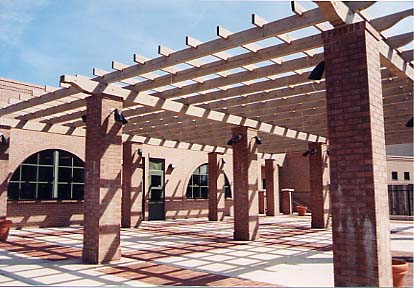

A second exterior feature that bears Gorlin's stamp is an elegant permanent sukkah on the south side of the property. Drawing on the vocabulary he first developed for the pergola of Villa Marittima, a seaside residence, Gorlin matched the pillars he developed for the welcoming front entrance of the Synagogue and laid an arbor of crossmembers above them. The painstaking quality of his work came clear as his team developed alternatives for the precise contours of each endpiece. The final result is a deeply pleasing, sunlit structure beautifully harmonized with the rest of the building. It serves a multitude of uses in the course of the programming year and is a great favorite of members and friends of the Synagogue.

Gorlin's most profound achievement lies in the redesign of the Sanctuary. The original complement of seats was slashed nearly in half and rearranged in graceful radiating arcs. Two freestanding screens punctuated with small frosted glass windows narrow the Sanctuary and build volume for congregational singing. On the north side, the screen does double duty by shielding the long ramp for handicapped access to the bimah. A small extension or "tongue" of the existing bimah allows close contact between officiants/celebrants and worshippers. Finally, Gorlin pierced three walls of the original structure to create an ingenious set of windows that flood the Sanctuary with natural light.

Mindful of the original budget for the project, Gorlin gave much more than the Commitee imagined possible, and hinted at what it might accomplish in the future if it were willing to tackle the aesthetic problems of the existing Ark. It was that exchange, among others, that helped seal the relationship. The Committee came to feel strongly that Gorlin could be counted on to honor the real-world complexities and context of the project.

As always with such undertakings, there were many creative people who had a hand in bringing the new building to completion. The congregation expresses gratitude to Alexander Gorlin's staff, most especially to Glenn Goble for his exquisite draughtsmanship and taste. Carolyn Fielder of Campbell Design in Tulsa was instrumental in shaping the final look of the building and continues to be involved in the choice of finishes and furnishings. Both were inspired by Alexander Gorlin's original vision and helped translate it into a living and working building.